The International Canoe

~ from Uffa Fox Sailing Boats ~

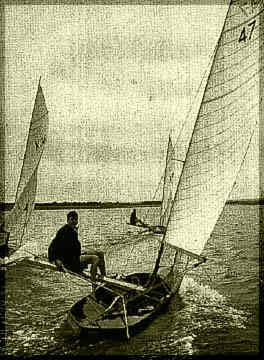

The sliding seat canoe is known as the 'dry fly of sailing'. One man or woman has to handle the jib, mainsail, drop keel, tiller and sliding seat. It has always astonished me that those who organise the Olympic Games have not chosen this as the single-handed boat, for the Olympics are supposed to be the high water mark of skill, and no other boat calls for such sailing proficiency as the International Canoe. No other single-handed boat can match them in speed or movement as they slip along with the grace of an ocean bird.

Some twenty-five years ago, I entered the canoeing field and at the Royal Canoe Club's Annual Meet won the two most important trophies, the Challenge and the De Quincy Cups. For the first time I introduced the deep chested V-d type of planing hull into the canoe world. The following year, 1933, I went with Roger de Quincy, a keen young canoe sailor, still at Oxford, across the Atlantic in the old Empress of Britain with two canoes: Roger's Valiant and my East Anglian, both sister ships. We were trying to bring back the 'New York Canoe Club International Trophy', the two Canoe Championship Cups of America as well as some of their other trophies.

The American canoe rules at this time were different from those of Britain. We had the disadvantage of building a canoe to fit both the British and the American rules, but in spite of this, we hoped that our planing lines would give us such superiority that we should be successful with our challenge.

We landed at Quebec, and took the train through to The Thousand Islands and joined the American Canoe Association for their Annual Meet, on the island they own, 'Sugar Island'. Then we rigged our canoes and started racing.

With three firsts and three seconds in six championship races, I won the two National Championships of America, The Sailing Championship and also the Combined Paddling and Sailing Championship, and with three silver and three bronze champion- ship medals, had now enough decorations to attend a British Legion dinner without feeling too naked. Roger won the Paul Butler Trophy and also the Murphy Howard Trophy. For the most part we were blessed with strong wind, a fair amount of windward work and planing reaches, under which conditions our canoes were invincible.

After this we went south to Long Island Sound, and here, by winning two races out of three, we won the New York Canoe Club's International Trophy. This was the first time that this trophy left American shores, though it had been raced for since 1886. Although such eminent canoeists as W. Baden Powell and W. A. Stewart had challenged for it America had, until 1933, defeated all comers. Having shown that a boat could be designed to two distinct rules, and still win, we had meetings with the Americans asking them to change some of their rules on condition that the Royal Canoe Club of Britain changed some of theirs so that we could have an International Rule for canoes all over the world.

Fortunately, the Americans saw the wisdom of this argument, and we soon roughed out a rule which would develop a wonderful canoe. We chose the best points of the American, Swedish and British rules to make this new International Rule, and when we brought this to England the Royal Canoe and Humber Yawl Clubs approved, with a few minor alterations. So Roger and I, as well as winning all the important canoe trophies of America, brought about an International Canoe rule which has remained in force and given great international sport from then to this day.

The International Canoe Rule meant that canoes could be between 5.20 m = 17' 0.75", and 4.87 m = 16' 0" in length. The canoe could not be narrower than .95 m = 3' 1.375" or wider than 1.l m = 3' 7.25". The depth of hull not less than 5 per cent of her length .30m = 11.25". The rise of her bottom amidship not more than .102 m = 4" at .4025 = 1' 4" out from the centre line. The minimum weight of the canoe stripped of all removable gear 60 kilos = 129 lb. The drop keel not to extend below the hull more than 1.0 m = 3' 3.375". The top of mainsail not to be more than 5.8 m = 19' above deck, or the jib more than 4.27 m = 14' above deck and the actual area not to exceed l0 square metres = 107.64 sq. ft. The sliding seat not to extend more than 1.524 m = 5'. Then as a safety factor a positive buoyancy is required of 45'36 kilos = 100 lb.

Within two years, Gordon Douglas of the American Canoe Association, sent his challenge to the Royal Canoe Club for the New York Canoe Club's Trophy, and his canoe showed that the Americans had not learnt any of the lessons of East Anglian and Valiant. Though Nymph II was wider than usual in America she still had the ketch rig, that is, the mainsail, the largest sail, forward and the mizen, the smallest sail, aft. Although he brought over our cutter rig, Gordon was continually changing from one to the other with no confidence in either. Nymph also had a typically American characteristic - immediately the mast was stepped, the boat had to be held upright, for her lines were so unstable that she would capsize with just her bare poles. Whereas our boats always sat upright comfortably on their moorings, and while the finer lines of the American canoes made them faster in light going, our fuller bodied boats had a much higher maximum speed and were bound to win when there was any wind.

Roger de Quincy was chosen by the Royal Canoe Club to defend, and this he successfully did in Wake, a stable planing canoe. Before Gordon left for America, I gave him the complete plans of Wake so that he could realise the wonderful qualities in such lines and give the American canoeist a fresh start. If the winning boats' lines are always given to the defeated, it is a great encouragement for them to try again, after improving their own vessels, This is all to the good of international sport, and if I made the rules for such sport, my first would be: 'The defeated vessel to be given the victors' plans so he could go home, encouraged to try again now that he had the winning boat's lines, construction, masting and rigging details. The Americans repeatedly tried to take back this trophy and in spite of Gordon Douglas building a canoe Foxy Nymph on the lines of Wake in the following year, and winning all the important American Canoe trophies, whenever the Americans came over to us they did so in non-planing canoes and we held the trophy in Britain for just on twenty years. Then, lo and behold, our Canoe Club chose a canoe that I had not designed, and the Americans' canoe was successful in its challenge and the New York International Trophy now rests in America! There is every prospect of a challenge going out from the Royal Canoe Club in the summer of 1959.

The canoes have gradually developed from the Eskimo kayak and Canadian paddling canoe. At first, when sail was put on them, the canoeist sat inside, then on the deck. Then Paul Butler of America, who was quite a small man in stature, as well as being crippled, found that he could not win races against the heavier men, so he put the old Indian plank on his canoe, and started to win. Others, of course, had to adopt this idea. So the sliding seat canoe came into being, and when Roger and I went to America with our canoes we had to convert them to sliding seat canoes.  The Americans did not allow side stays on their masts and at this time all their canoes were ketch rig, with two thirds of sail in the mainsail forward, and one third in the mizen sail aft. Living in a country on the lee side of the Atlantic where it is important to be able to go to windward, we in Britain are ever mindful of the weather-going qualities of a boat. I naturally designed a canoe for American waters, cutter rig, and did this by putting their spar of the mizzen in the fore part of the boat, and raked it aft so that it joined the main mast at the top. So, though we were to the American rules, with no side stays, and a proportion of two thirds and one third in the two sails, we were able to have a cutter rig. It was not until I arrived in America that it was explained to me that the object of these two rules was to force all canoes to have ketch rig. I said, 'Well, if that is the object of the rule, why not say so".

The Americans did not allow side stays on their masts and at this time all their canoes were ketch rig, with two thirds of sail in the mainsail forward, and one third in the mizen sail aft. Living in a country on the lee side of the Atlantic where it is important to be able to go to windward, we in Britain are ever mindful of the weather-going qualities of a boat. I naturally designed a canoe for American waters, cutter rig, and did this by putting their spar of the mizzen in the fore part of the boat, and raked it aft so that it joined the main mast at the top. So, though we were to the American rules, with no side stays, and a proportion of two thirds and one third in the two sails, we were able to have a cutter rig. It was not until I arrived in America that it was explained to me that the object of these two rules was to force all canoes to have ketch rig. I said, 'Well, if that is the object of the rule, why not say so".

As the sail plan shows, the boats today are very efficient, with a workman-like cutter rig with the top of the mainsail to the limit height of 19' above deck and the top of the stay, on which the head sail is set, 14' above deck. Such a mast 2' in diameter and round in section, with walls, only weighs l6 lb. So there is very little aloft to upset a canoe in the way of weight and windage. The 107 sq. ft, allowed is made up by 25 sq. ft. in the headsail and 82 sq. ft. in the mainsail. The main boom, well off the deck, gives the helmsman a clear view all round whilst, a most important point, the boom is high enough to clear his head as he sits on the slide.

The canoe design, illustrating this chapter, shows the fast planing canoe of today. The original rule said that no sections could have a radius of less than three inches, but this was later amended so this canoe now has a round bilge forward and a chine aft.

Canoes sailing to windward or in light weather are travelling at a speed equal to the square root of their waterline length, or slower with the chine aft out of water. At such a low speed, the minimum wetted surface is important, so she has a round bilge for three quarters of her length.

Canoes sailing to windward or in light weather are travelling at a speed equal to the square root of their waterline length, or slower with the chine aft out of water. At such a low speed, the minimum wetted surface is important, so she has a round bilge for three quarters of her length.

Off the wind in a fresh breeze, or a wind of greater force, she travels at up to four times the square root of her waterline; then it is that the chine aft tells its tale, for where the water clings to a round, it cuts clean away from a sharp corner. The chine also extends the planing bottom outwards and gives greater planing power.

These canoes must, by their rules, be 1l' deep amidships, and it will be seen on looking at the lines that the sheerline gradually rises to the stem to take her through and over the waves. Back aft, there is only 3' of freeboard for these boats, and their very easy lines do not disturb the water at all, and so are never in danger of being pooped. They iron the water out flat so there is no need to have a high stern, and a low stern like this means that there is very little windage aft and the wind does not, therefore, tend to stop the boat as it flows off this low stern.

Because speed is a function of the length, and the finer the lines, and the narrower the boat, the faster she is, most canoes today are to the maximum length and down to the minimum beam allowed. This canoe is l7' x 38' x 1l' deep x 129 lb, the minimum weight allowed but with the maximum sail area of 107 sq. ft.

From the stem to the mast, and back to the shrouds, she has a high turtle deck, which helps her in a seaway, keeping her dry and buoyant. Also, because the mast height is taken from the deck at centre, it has the effect of giving her a taller mast by the rule, thus enabling the helmsman to have good headroom above his head for the main boom. Abaft this, the deck is dished down into a hollow, as this gives the canoeist leg room under his slide and also drains the shipped water out through the centreboard slot, and the slot through which the drop rudder is rigged.

The drop keel needs no explanation as it is exactly the same as that rigged for any other boat. This boat is too long to have a rudder hung on the stern as in that position it would be too far away from the drop keel for maneuverability. There is a frame made therefore to take the rudder bar, and once the rudder is fixed into this frame, the rudder and the frame can be slid down through the deck. The frame represents the keel at the bottom and the deck at the top, thus enabling an underwater rudder to be shipped and unshipped.

This rudder also has another advantage, for a rudder hung on the stern, or a propeller abaft the stern, suffers from cavitation, whereas a rudder under the bottom of the boat is in solid water, and no air can get to it unless the boat is heeled a long way. This rudder is more effective than one on the stern and can therefore be of a smaller area, so easing up the wetted surface,

These canoes with their fine lines - finer than any other boat - their light weight, and their sliding seat extending five feet over the side, thus enabling the helmsman to get right out to windward, are the fastest sailing boats of their size in the world, and reach phenomenal speeds. Their acceleration is tremendous and in addition to this thrill there is the joy of being outside the boat and being able to watch her cleave her way through the water cleanly. It is not surprising that those who have flown low over the water on a sliding seat are enthusiastic about the 'dry fly of sailing'. There is nothing I know to equal it. There is the feeling of speed, and the clean rush of air, as the water rushes swiftly underneath you. There is also the joy of gliding low and swiftly over the water, the only sounds being the swish of your canoe through the water and the singing of the wind through your mast, rigging and sails. At sixty, though I am now too old to enjoy this, I still look back with a quickening pulse and tingling of the blood at the exciting moments on the end of a sliding seat in a lightweight canoe. I am very thankful that Roger de Quincy and I, twenty-five years ago, were able to bond together canoe sailors all over the world with one International Rule.

Back to Historical Archives

The Americans did not allow side stays on their masts and at this time all their canoes were ketch rig, with two thirds of sail in the mainsail forward, and one third in the mizen sail aft. Living in a country on the lee side of the Atlantic where it is important to be able to go to windward, we in Britain are ever mindful of the weather-going qualities of a boat. I naturally designed a canoe for American waters, cutter rig, and did this by putting their spar of the mizzen in the fore part of the boat, and raked it aft so that it joined the main mast at the top. So, though we were to the American rules, with no side stays, and a proportion of two thirds and one third in the two sails, we were able to have a cutter rig. It was not until I arrived in America that it was explained to me that the object of these two rules was to force all canoes to have ketch rig. I said, 'Well, if that is the object of the rule, why not say so".

The Americans did not allow side stays on their masts and at this time all their canoes were ketch rig, with two thirds of sail in the mainsail forward, and one third in the mizen sail aft. Living in a country on the lee side of the Atlantic where it is important to be able to go to windward, we in Britain are ever mindful of the weather-going qualities of a boat. I naturally designed a canoe for American waters, cutter rig, and did this by putting their spar of the mizzen in the fore part of the boat, and raked it aft so that it joined the main mast at the top. So, though we were to the American rules, with no side stays, and a proportion of two thirds and one third in the two sails, we were able to have a cutter rig. It was not until I arrived in America that it was explained to me that the object of these two rules was to force all canoes to have ketch rig. I said, 'Well, if that is the object of the rule, why not say so".